The 11th of February is celebrated annually as the international day for women and girls in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics). Instituted by the United Nations General Council, this day is marked to celebrate the contributions of women in science, and inspire new generations of girls into pursuing STEM careers.

As a woman in STEM, this was news to me.

****

What does it mean to be a woman in science?

In an ideal world, there should be nothing special about being a woman and pursuing science. That I am a scientist and a woman are entirely coincidental. In other words, there should be no implicit or explicit bias or expectation of me, as a woman, to pursue or not pursue a certain career.

Yet, there are many biases. Across societies and cultures, it is amply clear that women are expected to be the kitchen-runners and house-keepers and silent spectators, while men are meant to go out and perform actions and duties and run the world in general.

And also do science.

Of course, in today’s ‘progressive’ world, women are expected to juggle both without any complaints.

They didn’t like her much at her new school; she acted oversmart and asked too many questions. The boys didn’t like her because she intimidated them, the girls didn’t like her because she didn’t know when to shut up, and created more problems for them.

Sometimes she still wonders if she is too much for the world.

The reason why it doesn’t matter to me is because I find the celebratory messages repetitive and perfunctory. There is no heart in the messaging, no personality; just scores of social media posts with women scientists glorified simply because it’s supposed to be their day.

Year after year, even the women who are in the spotlight remain the same. They have the same stories, similar struggles and privileges that got them to scale the heights they have today. Don’t get me wrong, I am not belittling their journeys. But at some point I have to ask, how often am I expected to read their stories and be inspired?

For once, I would like to know about their scientific accomplishments when it’s not International women’s day or International day for women in science.

She was listening intently to a junior researcher presenting his data. Some of what he was saying was inaccurate, and she wanted to correct him, lest those ideas become ingrained in him forever. She waited patiently for an opening, mindful of not disturbing his presentation flow. As she waited, she debated whether he would benefit from an interruption now, in front of everyone, or would it be wiser to talk to him later, when he would anyway be more receptive. As she was silently wrestling with these thoughts, another colleague chimed in, corrected the student, and while the student was visibly flustered, thanked the senior colleague and moved on.

She just sighed and moved on too. After all, no malice was intended.

The burden of empathy is always hers to bear. Will it ever change?

Immortal, yet forgotten

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks died of cervical cancer, but her cells live on. Her cells, dubbed the HeLa cells, are immortal and have powered biological research through decades. Biotech companies have profited off of them, research labs obtain grants based on results obtained from experimentation on her cells. Yet all her family wants is that she be remembered as a person, not some cell line.

For the longest time, no one knew who Henrietta Lacks was. No one cared.

Her cells were taken from her without any consent.

She was an African American woman. How many people have directly benefitted from her? How many are willing to acknowledge?

One time, I had some early morning work in the lab. As I entered sleepily, three women were chatting busily in Spanish, oblivious to my presence. They were the cleaners – in charge of ensuring our lab spaces remain spick and span. They smiled when they saw me, and continued about their business. I was reminded of similarly happy, carefree cleaners in my old lab, twelve thousand kilometers away.

Don’t these women contribute to science just as much as you and me? While we test hypotheses and write papers, they ensure that our results aren’t contaminated by dust.

Perhaps it’s time we listened to their stories and be inspired in new ways.

Rosalind to Rosalind: The cycle continues

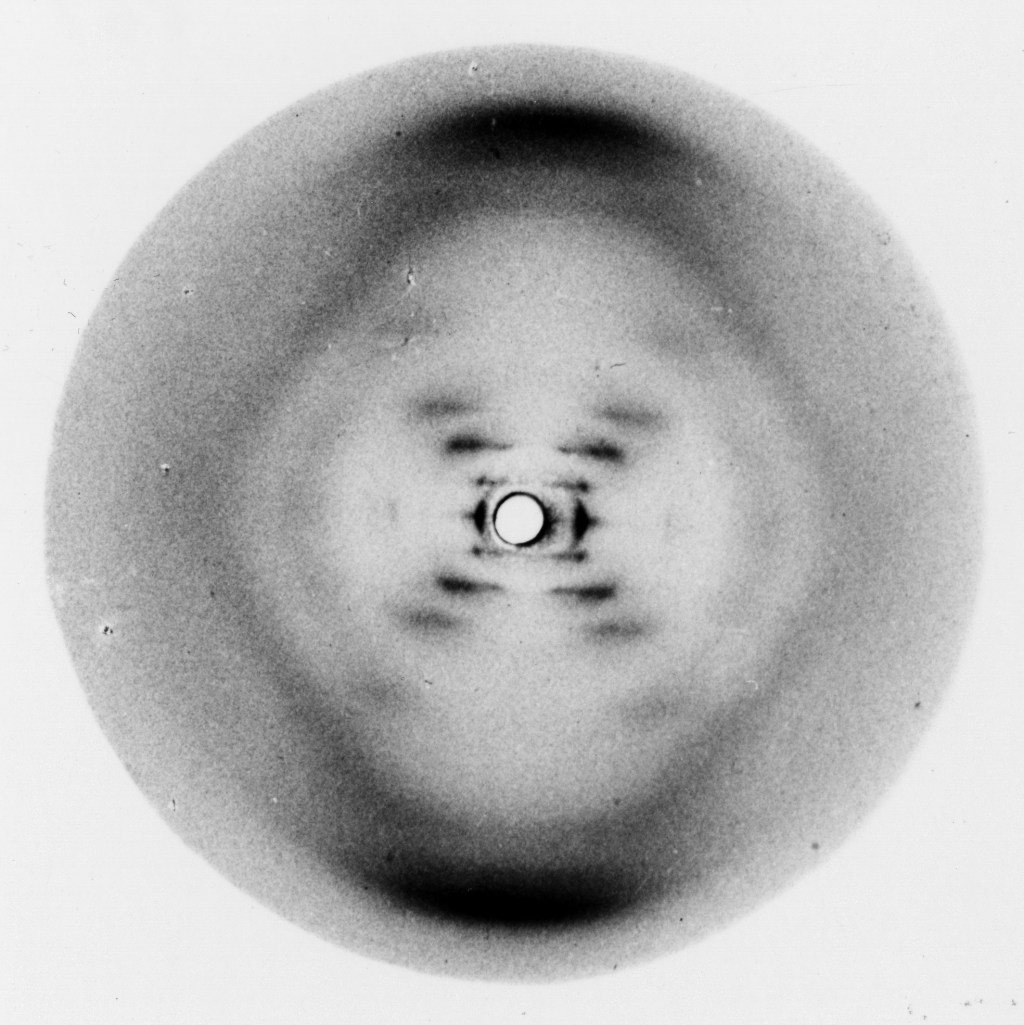

In 1953, four scientists discovered the structure of DNA, the fundamental unit of our genetic makeup, and changed the course of biological research. One of the four, Rosalind Franklin, was responsible for the collection and interpretation of key data that proved to be the decisive piece of evidence needed to solve the structure.

Source: Raymond Gosling – King’s College London Archives: KDBP1/1/867. Taken from “The double helix: “Photo 51” revisited” by Thoru Pederson

The others, her male colleagues, often neglected her, had discussions without her, and famously also had access to her data without her knowledge. Franklin died in 1957, which effectively robbed her of the Nobel Prize awarded to the other three scientists in 1962 (because the Nobel Committee doesn’t award the Prize posthumously, a reason which has been brought up repeatedly whenever this story is discussed).

If you think I am bringing up sexist stories from the 1950s, then here’s a more recent one. In 2024, the Nobel Prize for Medicine was awarded to Victor Ambros. His wife, Rosalind Lee, the first author on many of the publications that earned him the Nobel Prize, was of course, ignored.

The gender distribution of Nobel Prize winners is shocking even for someone like me, who is very well aware of this discrepancy. From 1901 to 2024 in the STEM fields, 912 men and 65 women have won the Nobel Prize.

****

I am not saying that I am not to blame. I am also biased against people of my gender, and worse, of non-binary genders, as much as the next man. I cannot name even a single non-binary scientist I know of.

Though I think, and I hope, that this says more about the state of affairs than it says about me.

She let go of an important data point because she felt unsafe going into that dark room all by herself at night.

These stories I have highlighted are not mine alone. Many have similar experiences, or worse. There are many more stories to be heard, many more perspectives to be uncovered. The recognition through a commemorative day might feel nice momentarily, but it is not enough.

We must be open to examining our own biases, and correcting our attitudes and behaviors. We must also be mindful of not letting initiatives that promise change become tokenized. Women, non-binary people and other minorities should be in leadership positions driving the change they envision. But the responsibility of bringing about the change has to be borne by all of society. It’s exhausting to talk about this, raise awareness, and be also tasked with the heavy lifting.

****

I want to end on a positive note – by highlighting this group of field researchers discussing the difficulty of managing their periods while performing fieldwork. Fieldwork can be challenging physically and emotionally, and it often takes place in remote areas with limited access to proper sanitation. This is an important conversation to be had, and people should be allowed to voice their experiences and opinions without fear of judgement or any taboo. Despite the cringes and stares they received for talking openly about these issues, they spoke up, and I am glad they did. This is but just one everyday biological experience of womanhood. There are many, and we must talk about all of them.

Perhaps real progress begins when these conversations are no longer brave, but simply normal.

Leave a comment